Back in the 1980s and 1990s the security industry was a very different place. Perhaps not so much the static sector, but door supervisors, or “bouncers” as they were mainly still referred to back then, were a law unto themselves. Now there were many fantastic, and professional door staff back in the day, and I will most certainly not generalise, but there was also a very shady section of the security workforce, who were quite frankly, a menace, and a danger to the public.

After a few big newsworthy incidents, highlighting the behaviour of some of these less than fully above board, doormen, the Government decided to act in order to protect the general public and remove the criminal element from the private security industry.

This led to the birth of the Private Security Industry Act 2001.

What is Private Security Industry Act 2001

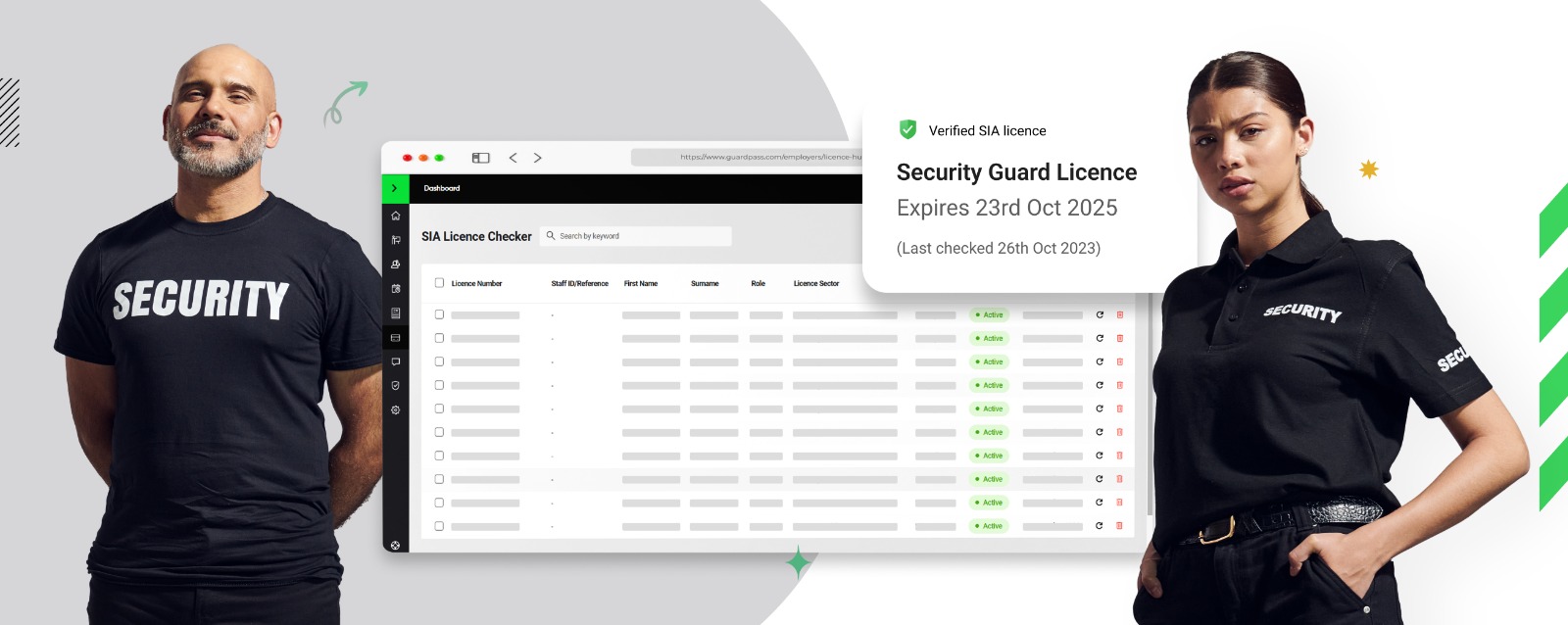

This Act of Parliament required the formation of an industry regulator, answerable directly to the Home Office. The Security Industry Authority, or SIA, was born, and charged with the role of protecting the public by means of two new mandatory processes. Firstly, every UK security officer, in every sector, would have to take and pass a basic security training course. Secondly, once training had been successfully completed, a licence would be required for every individual. These licences have to be renewed every three years.

Most importantly however, to assist with the PSIA’s stated goal of public protection and cleaning up the security industry, each person applying for a licence must undergo a DBS (then called the criminal record office) check before a licence can be granted. Licence costs have gone up and down over the years but average around £200, currently however, each licence costs £184. Still a lot of money to find for some of the lowest paid workers in the UK.

To ensure that the law is obeyed and that offenders are found and sanctioned, the SIA has an Investigations and Enforcement department, charged with tracking down those working without a licence or the correct licence for the role they are performing. They are also responsible for prosecuting companies that employ or utilise unlicensed security officers, a fundamental requirement of the Private Security Industry Act. Most recently, there has been a serious issue with mandatory SIA training malpractice, and the Investigations division is working hard to bring the offenders to justice.

SIA’s Limitations and Potential Improvements for the Security Industry

A typically long winded document, the PSI Act, allows the regulator little leeway to do very much else. I have heard some say that the SIA should introduce minimum pay rates for licensed security workers. They can’t. It’s against the law, and way beyond the scope of the Act of Parliament that created them. A couple of years ago I even witnessed a few misguided individuals attempt to set up “a new privately run alternative to the SIA”. Erm? Only if you change the law to allow it my friends.

Frustratingly there are a couple of major things that the SIA CAN do to help improve the industry:

- Follow the lead of the Gangmasters and Labour Abuse Authority, and publish a minimum charge rate framework, clearly setting out the level, below which questions need to be asked about the legality of the company accepting such low rates.

and…. - Introduce mandatory licensing of all security companies. This would create a hurdle for the less scrupulous security service providers to jump, and more importantly, allow the reporting, investigation and removal of those companies that still attempt to act illegally.

So what is stopping them? In three simple words, the Home Office. The SIA has asked for authorisation to implement these important initiatives. The industry has been pleading for these changes. So why does the Home Office ignore these calls? This is the $64,000 question. It is fairly obvious that there are certain large “traditional stakeholders” currently doing alright thank you, and that have a vested interest in maintaining the status quo. Whose ear do they have at the Home Office?

Reforming the Private Security Industry Act: Needed Changes

Does the Private Security Industry Act need reform? Yes. It even refers to all licensed sector workers as “security guards” much to the annoyance of organisations like the BSIA, Security Institute, IFPO, IPSA, and the Security Commonwealth that have spent a lot of time and money trying to get the term replaced with “security officer” to remove the negative connotations that hang over the former term.

There are also new responsibilities that the industry will have to shoulder around the increasing terrorist challenge, and potential new legislation designed to mitigate this threat.

For now the PSIA remains a tool born out of the problems of the last century, designed to protect the general public from an industry that, in places, resembled the wild west. It can’t be changed overnight, and frankly, there seems to be very little political will to reexamine the subject at all, so for the time being, manage your expectations, and acknowledge the PSIA’s limitations.

For those that would like to have a look at the most recent version of the Private Security Industry Act 2001 in full, you can find it here: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2001/12/contents

Estimated reading time: 5 minutes